According to myth, Roman inflation ends Roman empires. According to me (and a barrage of evidence), I’d like to see someone try to prove it.

When did the Roman Empire fall? I was led to the question by the claim that inflation caused the fall of the Roman Empire (476 CE). Except I looked a little too far into it. The historical void looked back. We lack satisfactory evidence to be absolutely sure of almost everything. Often, what we do know comes from only one source, and must be taken uncorroborated and with a grain of salt. Sometimes our authors are from a century or more after the fact. Occasionally – very occasionally – we’re lucky enough to get enough sources that they can actually conflict. I’ve tried here to stick to archaeological evidence as much as possible, apart from the political timeline. With economic and numismatological (“of the study of coins”) data, this leaves us on some stable footing. The rate of coin debasement is strongly attested to in the numismatic record. Other archaeological data will give us windows into the changing economic environment of the Empire.

So today, we’re launching straight into the idea that launched a thousand tangents. Coin debasement. Hyperinflation. The fall of the Western Roman Empire. I will refer to the bunched concept as debasement-inflation-fall from here on out, or DIF. It’s a startlingly persistent idea, but its order, you’ll find, is stretched beyond all credibility.

Debasement→ Inflation→ Fall?

In early economic thinking, silver and gold were value. Not just “valuable”: they were the measuring rod by which you measured the value of everything else. Silver in the pure silver coin, denarius; gold in the pure gold coin, aureus (which we will ignore from here on out, much like the actual Romans). How much was a pound of silver, except a pound of silver? How could silver be expensive, or cheap, when its weight was its own price? It was hard to conceive of silver having a value, except “less than gold” and “more than bread”. This wasn’t a supply-demand assessment. It was a ranking of what the Romans understood to be valuable. Silver was not the most valuable thing around by gram (think saffron, or purple dye) but it won out as the currency in much the same way that most cultures around the world seem to gravitate to precious metals as currency. Being easy to transport and to weigh, non-expirable, hardy, and unconsumable; also a universally attractive luxury good superflous to actual life that can work as a symbol of wealth instead. There will be a forthcoming article on fiat, metal and cloth currencies No one ever thought that the value of the measuring stick itself could morph and change.

So if the price of wheat doubled, then wheat had just gotten really expensive. If wine was now three denarii instead of one, merchants were simply taking advantage of poor soldiers. This pattern occurred in the French Revolution as well: where people come up against the unyielding iron of economic laws, they will attempt to blame them on the moral ones. Greed can be fought. Wheat shortages can’t.

The denarius could lose value if and only if it lost silver, Mixing in some brass to produce a 95% silver coin was almost unnoticeable, but it stretched an emperor’s silver supplies further, to more coins. This was called debasement. Now, according to a mercantalist’s position, debased coins masquerading as pure silver would be worth 5% less than they pretended to. Presumably, clever traders would notice that they were being swindled, and increase the prices of their goods to get as much silver as before (spread across more coins).

Except the mercantalist position was wrong anyway. You can’t eat silver. Currency is symbolic of wealth, and so the total goods and services (buy-able things) of a nation, divided by the amount of currency in circulation, dictates the value of the individual units of money. It is so much more complicated than this, but just imagine dividing an apple between 4 people with one dollar. Than four people with ten dollars each. Then four millionaires. The price of the apple goes up every time because there is (numerically) more currency. But in each scenario, whether four dollars, forty, or four million, the money can only be worth up to an apple. Both four dollars and four million were only worth one apple, because money is only worth as much as it can buy. No more. Now, imagine that apple is all the food, clothes, services and rent in the Empire. The combined money of everyone in the Mediterranean who can buy things (whether rich or poor) is the money supply. Money supply only matters for what it can buy. If aliens dropped 5 tons of silver in front of Emperor Septimius Severus, it still won’t manifest extra farms and wealth out of nowhere So why do we care about debasement when it’s the number of coins that matter, not what they’re made of?

Emperors successively debased coins (as far as 0.1%! Just a wash of silver over a bronze coin) for one essential reason: so they could make and spend more of them. No longer constrained by supply limits, the emperors could theoretically embark on wild sprees of reckless money-printing (or money-minting, in this case, for coins), distributing worthless bronze the same way we can imagine housewives of the Wiemar Republic forking over fistfuls of useless money-paper before giving up and finally just papering the walls with it. The boom in money supply leads straight to the sudden, sucking drop in money value. Voila, our first link between debasement and inflation.

Except that we have no evidence of this. Emperors did not record how many coins they minted – or those records are lost to time. We do not know how many coins were out circulating through the cities and settlements of the Mediterranean. I speculate that half the reason we spend so much time talking about coin debasement is it’s the only thing we have hard archeological evidence for. You can analyse a hoard of coins for silver content, but they won’t tell you how many more of them were out there (A predisposition to saving purer coins means that we can’t solidly establish coin commonality from our historical records and hoard finds. We’re guaranteed to find disproportionate amounts of pure, early coins compared to debased bronzes, but no way of establishing by how much).

For now, let’s allow the speculation and compare it to the data that we have. It’s a reasonable theory. Debasement allows excessive coin minting without the natural constraint of the silver supply, leading to sudden inflation.

It’s a pity that the data HAS NEVER BEEN FURTHER AWAY FROM AGREEING WITH REASONABLE THEORIES.

Let’s outline three different patterns we could take as support for this theory:

- Strongest : debasement directly corresponds to levels of inflation. (This is unlikely; it implies a constant supply of silver.)

- Moderate: Extra debasement roughly corresponds to either periods of low silver income and/or high expenditure, so inflation should roughly track debasement but may differ in magnitude. (i.e. low silver income may lead to high debasement but a normal number of coins added to the money supply).

- At minimum: inflation occurs during periods of debasement, give or take twenty years.

Actual outcome: INFLATION OCCURS A CENTURY AFTER DEBASEMENT. A WHOLE. JUPITER-DAMNED. CENTURY.

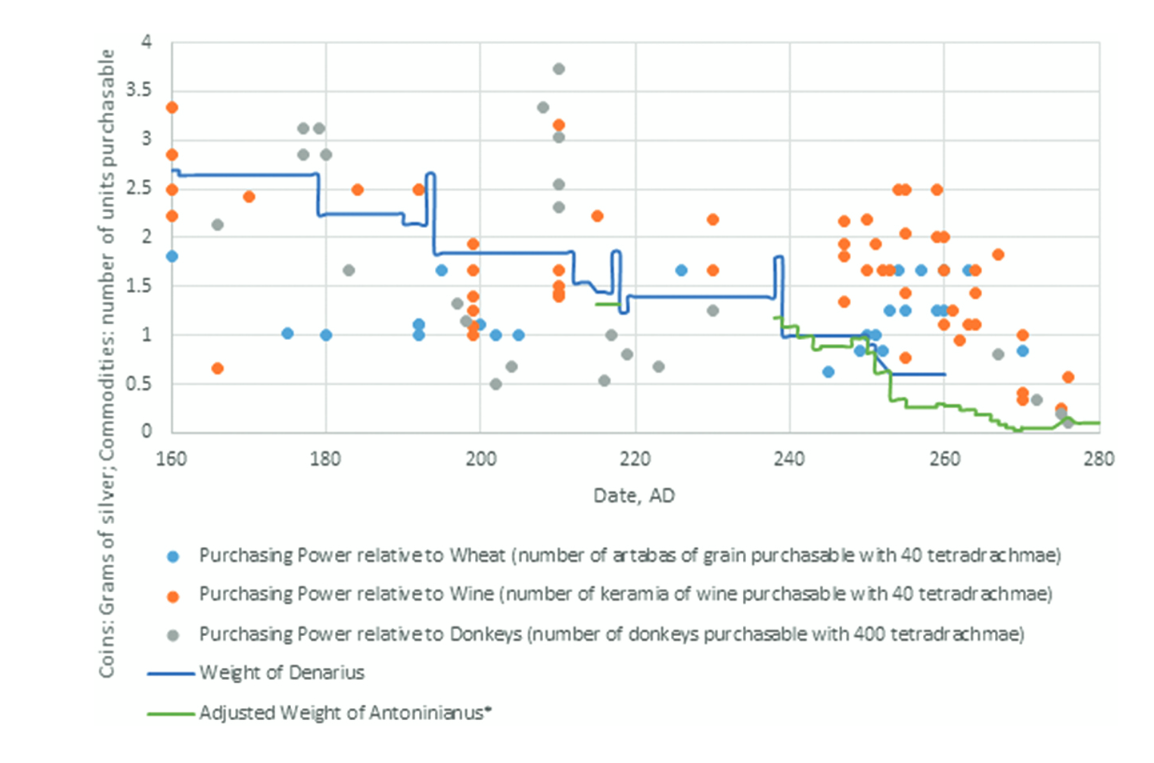

Purchasing power is pretty stable pre-270 CE; sometimes even increasing slightly in 210 and 250 CE. The same amount of money will buy 1 artaba of wheat or 1.5 keramia of wine across most of the century . Wine is very consistent, and wheat slightly more volatile. Donkey prices are all over the place and a touch wild; clearly the animal’s inherently contrary nature has infected the data. After 270 CE, however, purchasing power drops like a stone (the dots fall to the very right of the graph).

But look closely at these dates. Look at them!

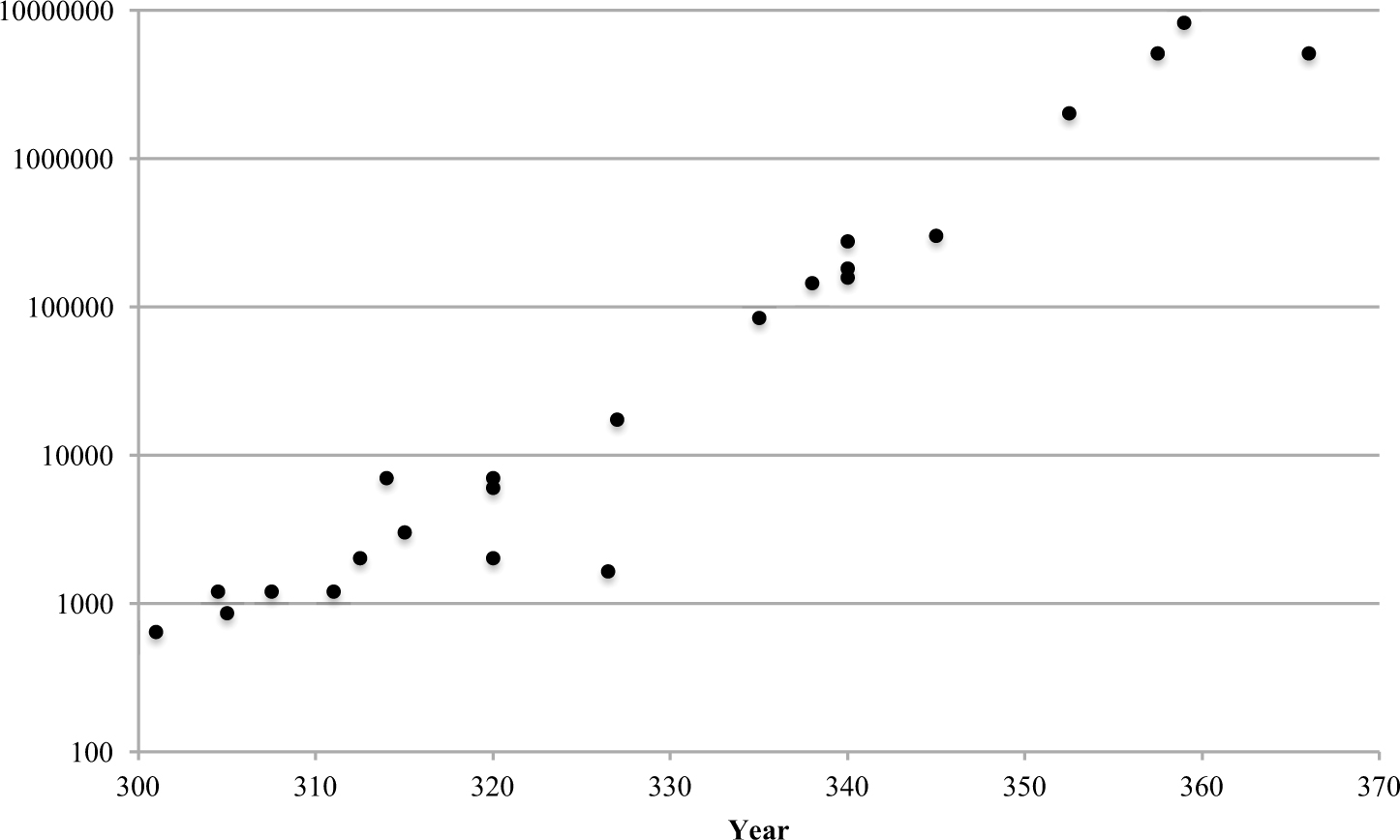

Debasement ends before inflation starts. Inflation starts only the very tail-end of a century-long process of blatant debasement, and then persists for at least a century. There’s another graph  demonstrating the exponential climb of prices through 300-370 CE because the above only shows 270-280 , but I’m trying to moderate my graph use.

demonstrating the exponential climb of prices through 300-370 CE because the above only shows 270-280 , but I’m trying to moderate my graph use.

Let’s add a political timeline to these conflicts. It will show us that inflation does not seem to reliably herald, cause, or accompany conflict.

We have the four dynasties (Julio-Claudian, Flavian, The 5 Good Emperors, and Severan Dynasties) until 235 CE. The coin’s at about 50% silver. And then the no-good, very-bad years of The Crisis of the Third Century. The coin nonchalantly continues its former downward trajectory, 41 men claim the title of emperor in five decades, and the empire nearly fractures into three parts.

Aurelian, Restitutor Orbis (literally: Restorer of the World), glues the fractals back together 270-275 CE, improves the coin to 5% silver, and then inflation starts. Diocletian takes the reins in 284 CE: this official ends The Crisis of the Third Century. He reforms and stabilizes the Empire. Everyone believes the good times have come again – people even have it written into the friezes of their walls. Inflation continues careening out of control. The Empire is relatively stable for at least another century.

(At least, there’s only ever a few competitors for the title of Emperor at once once every few decades, which is totally normal. Also a vast improvement on The Crisis of the Third Century.)

Summary of the Timelines

To bring all the timelines together: significant debasement starts in 190 CE; the coin is entirely bronze by 270 CE, after 50 years of civil war; civil war then ends in 270 CE, and inflation starts, persisting until at least 370 CE; around 364 CE the Empire splits again but is recombined, and then split permanently in 395 CE.

So, inflation doesn’t line up with debasement – they start almost a century apart. Despite rampant debasement, prices stay stable during one of the most intense periods of internal strife in Roman history, but only to begin skyrocketing as soon as the Empire is in firm hands and under a strong grip; and despite this skyrocketing inflation, the Roman political scene is (for Romans) relatively stable over the next hundred years. During a time where prices increase by five orders of magnitude.

One might wonder by this point if they should be skeptical of the debasement-inflation-fall argument.

Please wonder that.

But such a strong lack of relationship leaves us with questions as well. Why did debased coins hold steady? What triggered inflation? How could a leap in prices only representable on a logarithmic scale not have political impact?

I’m going to start with a slightly different question. Maybe we got our dates for “the fall” wrong. Our political timeline, at least, might be off, and the duration of an emperor’s reign may be no guide to the actual strength, integrity and resilience of Roman society as a whole.

The classic date for the fall of the Western Roman Empire places it in 476 CE, when the city of Rome fell to the Goths. I’d disagree. Delaying the fall of Roman society into the fifth century misses what made Rome “Rome“, to both its citizens and to history.

Rome as Civilization, Not Empire

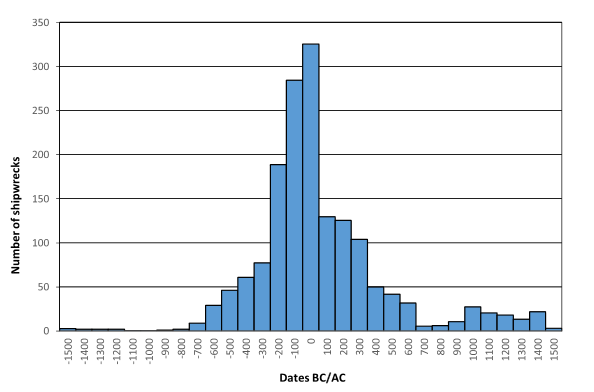

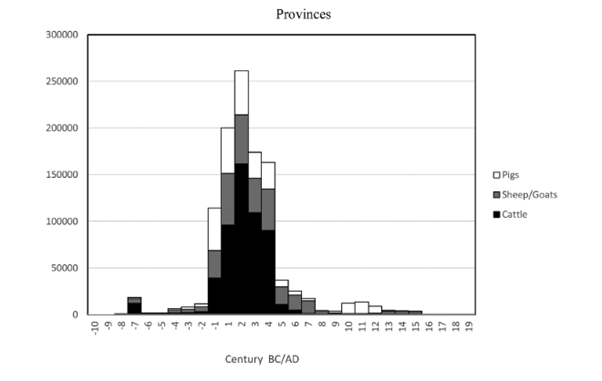

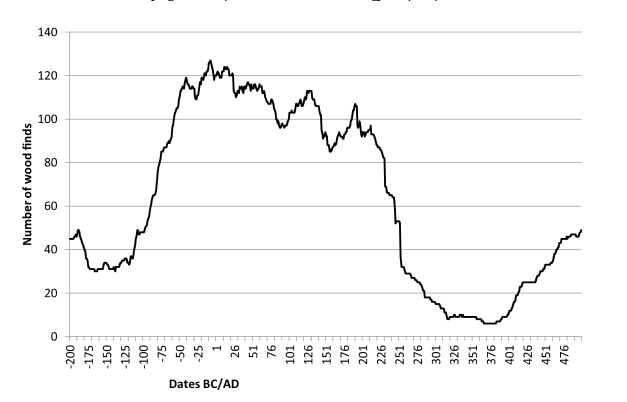

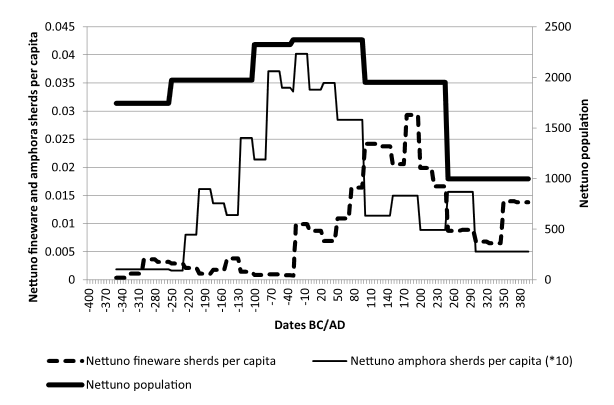

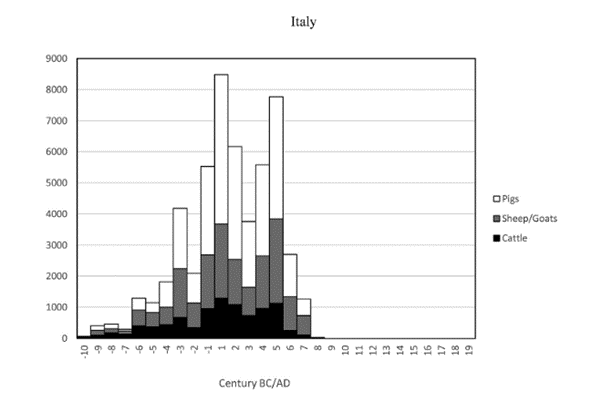

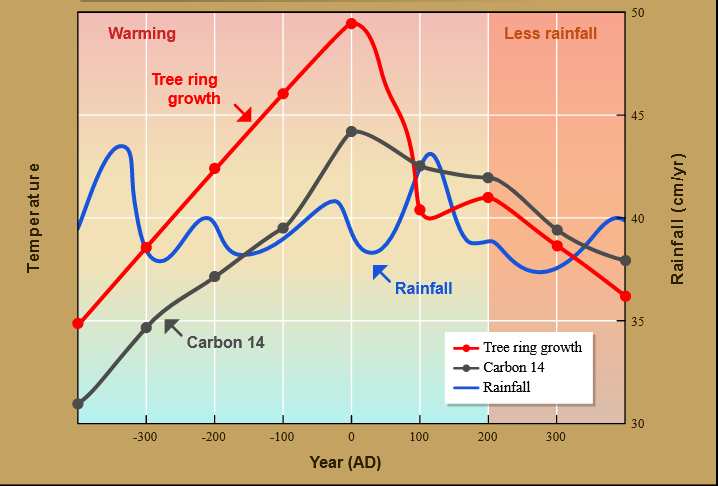

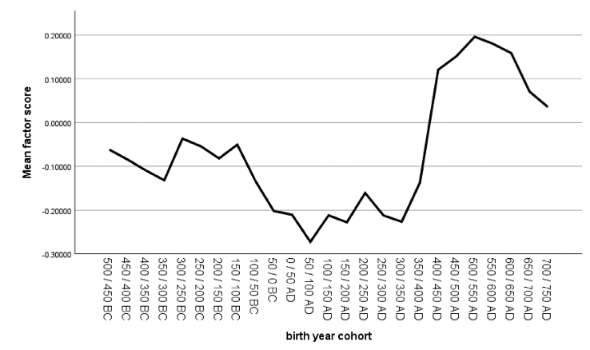

Have a look at the patterns in the following graphs: tracking the level of trade across the Mediterranean, fine pottery making in Rome, construction in Germany, meat-eating across the Empire, and climate trends for the period.

The absolute height of the Roman Empire was clearly in the first two centuries. This harsh bell-shaped rise and fall occurs everywhere, in almost every kind of data. That peak and harsh fall occurs at slightly different points, but they all point to a drop-off by 250-300 CE. What had been built by Roman civilisation was now just enduring.

Add to that this counterintuitive evidence from an unexpected source:

The material standard of living was higher during the first few centuries of the Roman Empire than any other. The same study that discovered this skeleton shrinking points out that not only does the number of domesticated animals increase at this time, but those domesticated animals literally grew in size during this period with better feed and conditions. Meat-eating was way up. But Romans were still smaller during the Empire than they were before or afterwards. The explanation offered by the study is pathogens. All roads led to Rome, which meant that Rome’s roads were direct vectors of disease across the entire Mediterranean. Increased mobility meant increased exposure throughout the Empire to every kind of disease from every corner. Local outbreaks never stayed local – a sentiment that we, in these COVID times, can appreciate. Increased trade and inter-connectivity brought greater wealth, but it did not bring greater health. Especially for the Romans, who had so little understanding of illness and disease that they literally had their toilets in their kitchens, all the wealth in the world couldn’t keep them healthy when they didn’t know how to use it.

Alternative theory: as population density increased, cow farming dropped in favour of pigs, goats and sheep. Cow farming moved out to less densely populated areas. This means the cities had no access to milk. Milk typically can’t travel further than 5-10km before going bad, which keeps it cheap, but it’s a nutritional powerhouse. Cheap+healthy = nutritional equaliser between the poor and the rich. That goes, and nutritional inequality increases, stunting average height. Another study controlling for proximity to cattle-farming found that height differences disappeared. As cattle-farming is also a proxy for population density and incidence of disease, this isn’t a slam-dunk defeat of the original study’s theory. But I do find the milk explanation much more convincing and causally more straightforward.

So a rather amusing result of the decline of Roman civilisation, trade, and production by 300 CE is that average heights improved. The study does break this down by province, and the East-West divide of the Empire (because remember that only the West fell) comes into sharp focus. The north-western provinces and western Mediterranean (e.g. Spain, France, Germany, Italy, both to their north and south on the Mediterranean coast) jump in height (and presumably health) after the third century. In the East, where civilization persisted and flourished for another thousand years, heights remained stubbornly low, and we observe only the briefest improvement before the East presumably re-establishes itself and its networks.

Keep in mind that this probably also represents a radical population drop in North-West Europe, which is less cheery.

Economically, then, the data points to the fall of Rome as a civilisation by 300 CE. Politically, could we spot any substantial political change?

Politically, Rome had just been through the wringer. The dread – and endlessly discussed, worthy of its special bolding – Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) lasted 50 years, during which 41 separate individuals had been declared emperor, and then declared dead. The empire was fracturing, the armies were mutineering, and it was power by the sword and not much else. By the end of the crisis, entire generations – most of the army generals – would have grown up with political chaos, assassinations, and endless civil war as the only norm they knew.

Into the breach stepped Aurelian, the Restorer of the World. Literally titled so by the Senate, Aurelian defeated two separate competitors for the throne and was forced to reconquer Brittania and the East to bring them back into the fold, literally reunifying the Roman Empire as it teetered on the brink of shattering into feuding pieces.

Unfortunately, he was assassinated. But he holds together the Empire for long enough for Diocletian to ascend out of the shards of the old order.

10 years after Aurelian’s death, Diocletian was yet another strong soldier-emperor. He would forever mark the Roman Empire by being an intelligent reformer as well. An astute politician with a strong desire for effective administration, he doubles the size of Rome’s public service, divides the empire into smaller provinces, sets up a legal system (where before the province relied on the governor’s arbitrary will), and elevates a fellow general to serve as his co-emperor. One to manage the West, one the East, setting in place that infamous division that will later define who stands and who fall with Rome in the next few centuries or with Constantinople (currently Byzantium) until the 15th. He revokes the Senate’s authority to declare or recognise the new emperor, vesting that right in himself and his heirs. He completely changes the nature of power, elevating the emperor to godlike levels of splendor, making him an object of reverence: rarely seen, rarely spoken to, absolutely obeyed. We call this new style the Dominate.

Where before Roman Emperors had playacted a fiction of being merely the princeps, the first citizen, a leader among equals, Diocletian wove a new theatre: one of untouchability, strength, and omniscient aloofness. Prior Roman Emperors might have walked the streets, pretended to speak to the common people, and acted as a leader among the people. Diocletian was lord over the people.

Unlike many of Diocletian’s economic and political reforms, the Dominate would survive, and set the foundations for the transformation into feudal society. Diocletian drew his authority from neither the Senate nor his Roman citizenship. With the assemblies and tribunes already erased from existence, there was now no trace of the Republic, of the pride and status of the Roman citizenry, the respect and the rights it engendered. Caracalla had made all freemen Roman citizens in one great stroke. But the grind of the following decades would sink the great and powerful ship of citizenship to a common raft adrift on the arbitrary political waters. Between the natural devaluation of citizenship and Diocletian’s new powers, he and his successors would be far more capable of suppressing citizen rights and blurring the line between free tenant and slave (creating the first serfs). The blow to Senate and citizenship undermined the most fundamental institutions of Roman culture. The rights over which earlier Romans fought wars were rendered pale imitations, powerless and meaningless ghosts of what they once were.

The serendipity of both major economic and institutional change dating to the same handful of decades is not something I can account for. Perhaps the princeps style of power could survive in one environment but the Dominate was required for another – the economic change occasioned immediate political change. Perhaps it’s just survivor’s bias – if Diocletian had not instituted the Dominate at just that moment, the political transition would have been the fall apart to a dozen tiny kingdoms. Perhaps it is just coincidence. Either way, the slow decline and the harsh transformation had both happened. We had gone from Republic to Principate to Dominate.

By 300 CE, as both an unusually advanced civilization, and as a cultural-institutional entity, Rome was done. The Crisis of the Third Century had merely been its final death throes.

But What About Tradition?

How could I forget the Goths.

I mainly discount 476 CE because it was not recognised as the fall of Rome at the time, but a century later, when Justinian (Emperor in the East) wanted a pretext to righteously invade Italy and take Rome, the cultural motherland, back. When Odoacer deposed the last Emperor in the West, and became the “King of Italy” instead, he sent the Imperial regalia to the East, with his respects. The East did not react – perhaps they just saw this as yet another change in ruler in the West’s tumultuous history. Odoacer claimed to be a “client” of the Eastern Emperor Zeno for the rest of his reign – talking about himself and his kingdom as an extension of the Eastern Empire.

Odoacer kept many of the Roman institutions. He literally ruled with the blessing of the Senate – in that respect he was more Roman than Diocletian! Odoacer consulted the same people the Emperors had. Wealthy Roman landowners had stayed where they were, and intermarried into Odoacer’s new regime. He had served in the Roman army before deposing another emperor. What’s more culturally Roman than leading an internal coup with a Roman army? The West, and its laws, and its culture stayed Roman.

I’m not arguing that no kind of fall ever happened. 5th century North-Western Europe is in really bad shape. They went backwards technologically, in population numbers, and their written records diminish. Rome is past its point of glory. But I think the fall must be measured by civilisation, not by political regimes. With no legitimate transfer of power, we’re drawing lines in the sand between the rulers we like and the rulers we don’t, and declaring some of them the last noble remnants of the mighty Romans, and some of them marauding barbarians who destroyed the our favourite empire.

Odoacer just doesn’t capture enough of the “fall” for me to worry over-much about 476.

It’s not even the last time Romans try to expand into the North-West. Justinian will prove that to us a century later. Nor was the fall guaranteed. Marjorian (dies 461 CE, just ten years before the “fall”) nearly salvaged the Empire, by many accounts, much the same way as Diocletian. If so, maybe the Empire in the West would have survived another hundred years.

Back to Inflation

Hyperinflation, caused by coin debasement, is often blamed as one of the “perfect storm” of issues that caused the fall of the Western Roman Empire over this century and the next. But as far as I can tell, this gives hyperinflation either too much credit or an excessively bad rap. The dates just don’t line up right.

But that still leaves us with all our earlier questions. Why didn’t inflation start earlier? Why did it start at all? Why didn’t it immediately destroy regimes? Also consider that the Dominate in the West got clawed apart in the century and a half following Diocletian. Why not the the East?

We’ll end up following a story of plague, crises of confidence, extraordinary measures and radical failure. Even in the modern era, inflation is a slippery foe. To the Romans of the third and fourth century, with no sense of monetary policy and an ever-hungry army, it was a kraken out of the depths: enormous, terrifying, and unfathomable.

For all that – see you next article!