Australia took on a lot of COVID debt. Like; a lot.

Financial year 2019-2020: a $85.3 billion deficit.

This financial year 2020-2021: estimated to be $161 billion.

Nor is it over yet. They’re forecasting next year’s deficit to the tune of $106 billion.

All of this is money that the government has to get from somewhere. All of this either is, or is going to be debt. The massive pile-on of borrowing over the next few years is expected to take us straight up to 1 trillion dollars of net debt in 2025.

Those are the raw facts, mostly without context, and this is where the scare articles (like below), begin:

Exclusive: A child born today will be paying for Australia’s COVID-induced debt bill until they are 31, according to @PwC_AU analysis for @theheraldsun. #auspol https://t.co/tXETHSpQYH

— Tom Minear (@tminear) May 2, 2021

This Twitter hook represents the article pretty well: discussions of the enormous debt taken on by the government during COVID are accompanied by doleful photos of a young family, alongside quotes from Treasury officials and high-profile employees reassuring the public that everything is absolutely fine and that Australia is recovering faster than even their best estimates predicted. All of this is loosely strung together, more by proximity on the page than by any line of argument.

The first fear is that debt is dangerous. It makes us financially insecure. The second fear is that debt is greedy. When the child in that article is 12, and 21, and 30, COVID debt will still be consuming resources that could have been invested in the Australian people.

The overwhelming fear is that we will be worse off for taking on debt, in some way, somewhere, at sometime.

A History of Aussie Debt

First thing to note: In 170 years, there has been only one ten-year period without any government debt at all. This was straight after federation, from 1901-1911. All the information on 20th century and pre-federation debt in this section is pulled from a Treasury (Budget Policy Division) paper by Di Marco, Pirie and Au-Yeung, “A history of public debt in Australia”.

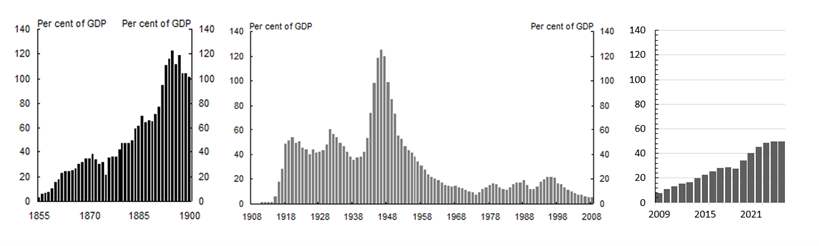

Before that was 1850-1900, when we were buying debt from the wealthy in London. We went from 3% of GDP in debt to 120% of GDP in debt in the late 1890s, borrowing more than all of (British) Australia could earn in a year.

After the stressors of the first World War, the Great Depression, and then the second World War, in 1945, despite a much bigger economy, our debt hit 120% of GDP again. But that’s the highest it gets. That’s the highest it ever gets. We pay off the bulk of it in the following years, and get gross debt down to an all-time low of 8% by 1974. Our debt has happily burbled its way along since then. It jumped by 10% of GDP after the financial crisis in 2008; for various reasons, it’s been slowly and steadily climbing since then. It was at 41% before the pandemic.

Now guess how hard a hit we took with COVID; how intimidatingly big that 1 trillion dollar debt will be, measured up against our economy and all the value we collectively produce.

50% of GDP. That’s all. Right now, we’re still just below 44% of GDP. We’ll just brush 50% on our way down in 2025, at the expected peak of a trillion dollars of debt.

We may be borrowing unprecedented amounts, but that doesn’t mean that we’re borrowing to an unprecedented level. Nor is debt itself unexpected. It has its own part in the cogs of governance.

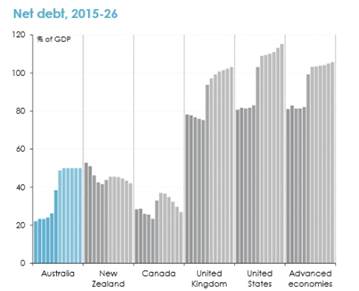

As a side-note, if 50% still sounds extravagant to you, see how that stacks up globally against other OECD countries. The graph is by Saul Eslake, 12 May 2021, assessing the 2021-2022 federal budget. Slides and Zoom recording available on his website: I would absolutely recommend watching it to understand Australia’s current economic state on a wide range of metrics and its implications. The data for this specific graph was pulled from the IMF Fiscal Monitor, April 2021.

The Name’s Bond. Government Bond.

Imagine you live in a science fiction. We can displace money across time. You turn twenty, walk into the bank (or more likely, open your banking app) and are informed that your forty-year old self has sent you a million dollars of their savings with explicit instructions to go buy a house. A million dollars richer, you pop down to a local house auction and land a new home. You’ll spend the next twenty years hosting dinner parties, introverting in your room, blasting music in the kitchen, and building your career as you put away the savings. By forty, you’ve saved that million dollars, and you know what you have to do. You pop down to the bank (they only do Time-Tubing in person, so retro) deposit the money and the instructions, and you no longer have access to a million dollars worth of savings. It was spent on a house when you were twenty.

The best thing about that scenario (apart from the fact that you’re the kind of person who’s going to earn over a million dollars in twenty years)? It’s that you will never pay one cent of rent. In the real world, if you want to spend only your own money, then you have to save a million dollars while paying a few thousand in rent every month. In the Time Tube science fiction, that unspent rent adds up to half a million that you’ll be able to spend on further education, jewellery, kids and vacations. You’ll save almost half the value of your house simply by borrowing money from the future.

The Time Tube fiction is interest-free debt. You’ve spent that money, so you have to make it, but there are no extra costs on top – it’s just the transfer of money from the future to the present, between yourself and yourself.

Australian student debt works like this. Without debt and the accompanying degree, you’d have to work for long enough to save for fees, but at a lower-paying job than you could get with that degree. Interest free student debt allows you to study, (theoretically) step into that higher-paying job immediately, and then pay off those fees more quickly before you continue earning for yourself.

This is what makes debt such a powerful and useful tool. The money to act now will save you money later. Of course, instead of borrowing from future selves, you and I have to borrow from wealthier people around us. They’re going to need reason to loan to us, and depending on how good a bargain we can strike, we’ll either promise to give them most of that half-a-million we’ll save by having a house, or only a bit of it.

Like a devil’s bident, debt becomes a twin-pronged issue: how much time do I have to earn the money I’m spending, and how much am I going to have to pay on top of that?

Let’s tackle the second one first. Interest rates ahoy!

Australian debt is issued in government bonds, called Australian Government Securities (AGS). You buy an AGS, and the government promises to give you that money back in ten years, and pay you a thin stream of interest every year, a percentage (e.g. 2%) of the initial amount, until then. Australian bonds are just about as iron-clad as it gets; if you give the government your money, you will get that exactly back, and you will get your interest. The corporate equivalent of bonds are stocks – buy a stock, and you may be able to sell it for the same or a higher price later, and if the company goes well, you may get a share of the profits (dividends). There’s greater risk and uncertainty, but greater returns. But everyone loses their taste for risk in a pandemic, and the world came flooding to Australia’s doorstep in pursuit of that iron-clad guarantee.

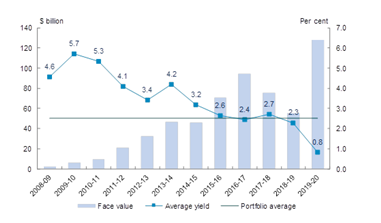

Don’t believe me? Here, from the AOFM (Australian Office of Financial Management), is a graph of the interest rate on AGS:

AGS are sold at auction. The government says how much they want to buy and for how long, and waits to find out the lowest interest rate someone is willing to separate with their money for. When money is plentiful and security is scarce, this invites a bidding war that drives interest rates to the floor.

From 30 March 2020 to 12 May 2021, we only borrowed $309 billion, but we could have borrowed over $1.13 trillion and only increased our highest interest rate by 0.04%. (Eslake)

At one particular auction, we borrowed $2 billion at an average interest rate of 0.12%. SMH Explainer, 29/09/20 “The trillion-dollar question: What is government debt and deficit and should we be worried about it?”. It’s also an excellent and informative run-down of the entire debt issue.

We’re pretty much setting the terms, and we’ve…pretty much broken the bident.

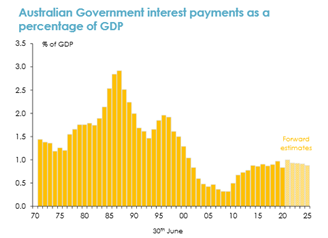

In 1985, gross debt sat below 20% and paying interest was eating up nearly 3% of GDP each year. Today, we’ve more than doubled our debt ratio to 44% and yet we’ve halved our interest bill to 1% of GDP every year. We are paying less in interest now than we were in the 70s and 80s. Any Australians reading this probably spent more of their childhood under higher interest bills than a child born today will ever get from COVID debt. Our interest payments were falling the year before the pandemic, and after 2020, barring further crises, massive borrowing or mismanagement, they are going to keep falling.

Australia is experiencing the next thing to sci-fi financial-time-travel right now.

Fine, fine, I hear you say. But there’s still one prong (Unident? Spear?). We’ve borrowed all this money, but do we have the time to earn it before we have to give it back?

Australia has spread its debt pretty widely, with “$13 billion of debt that is not due to be repaid until 2041, another $13.3 billion not due until 2047 and $15 billion due in 2051” according to the SMH. SMH, 25/05/21, “Debt problem? Not even a big rate rise will hurt the budget“. This article is also the source for the following paragraph and all information about S&P Global’s study, as S&P Global has chosen to be available only to professionals from listed companies.

Only 4% of our debt is due in the next 12 months. So we’ve got time. The real issue posed by short-term debt is that as the situation grows more stable, and people regain confidence in corporate markets, the short-term debt that we do buy (which is ongoing on the regular – while in deficit, the government runs AGS auctions a few times a week) will get more expensive. However, our low proportion of short-term debt is helping us there too. S&P Global has (reportedly) released a study stress-testing global debt in a scenario where interest rates jumped by a whole 3%. Even then, Australia’s interest bill would barely budge from 1.3% to 1.4% of GDP. This leaves us much better off than countries like Japan, whose debt is 38% short-term and would see their interest bill nearly triple.

Inflation Expectations

There’s one more ace in the hole, though this one’s subject to much more uncertainty. Inflation is a tricky beast, and not always predictable.

Inflation is the devaluation of money – when it takes more money to buy the same goods, across the economy (calculated using CPI, but don’t worry if you don’t know what that means), inflation is occurring. The price of fuel quadruples and suddenly all the food in the supermarket costs twice the price because transport got more expensive. Maybe iron ore trade with China sends $12.5 billion swimming into the economy and businesses start increasing prices because more people have more money to pay. Inflation’s great for debt – it’s great at making repayment less valuable, and great at making yearly interest less valuable. To maintain the value of debt, the interest rate on AGS has to be equal to inflation. If not, then the lenders are effectively getting less back from the government than they gave. Currently, inflation is just headed back above 1%, the Federal Budget papers are predicting 3.5% by 2022, and then it will hopefully stabilize between 2-3%, the RBA’s set inflation goal.

According to the AOFM in Figure 3, the average interest rate on AGS sold in 2020 was 0.8%. That’s below current inflation levels. That’s well under the RBA’s forecasted inflation. The value of Australian debt is going to erode into the future; we will be giving back less money than we are borrowing. In the article that began this entire discussion, the Courier Mail did one thing right: quoting PwC chief economist Jeremy Thorpe when he said that our debt is, in fact, “free money”. I’d go one step further. If inflation reaches the RBA’s expected target, the government will technically have made money off taking on COVID debt in 2020. They will “keep” some of the value handed over to them and never give it back. The lenders traded in more than just profit for security; they were willing to lose money for security, effectively paying the government a certain proportion of their loan for the rock-solid assurance of the rest’s repayment.

(Food for thought: Does that make COVID debt a form of progressive taxation?)

I follow the Federal Budget projections entirely here, but feel free to take this with a grain of salt. There are multiple opinions out there. However, the current inflation outlook is good and on the right trajectory, even if a little lower than planned. Most recent opinions seem to expect inflation to surge and then to settle, in line with the Budget projections.

I’ll be doing a more thorough breakdown of inflation and Australia in the future; keep an eye out for that if you’d like a more critical run-down of our future prospects.

(Edit: That’s now up, here)

So, in summary: debt and Australia. We’re not especially vulnerable to interest-rate rises. We’re not at risk of having to repay too quickly. The debts we’ve taken on are long-term, the very next thing to free of interest, and our interest bills are a single percent of GDP. We’re borrowing from the future to bolster our tomorrows, and despite having come through multiple lockdowns, a crash in tax revenue, and an explosion in welfare payments, we’re coming out on top. We did the right thing with debt, and we were well placed enough to do it really, really well.