Perot vs McCain vs Gepherdt: A Guide to Voting When You’ve Lost the Map.

by Rebekah Veykh

As a third-party president dancing a delicate ballet between a historic legacy and various political entanglements, President Perot has some experience with the ominous, overblown pronouncements of pundits and opinionated members of the public. Whether it was Eddie Reinbeck raging that breaking NAFTA was “a crime against free trade” and that Perot would be singlehandedly responsible for “reducing the world’s finest engine of economic progress to a third-world backwater”; or the Boston Review, meticulously documenting every policy that failed to pass Congress and pronouncing the past four years “the single most stagnant period in American legislative history”; or even the New Yorker, running a four page colour spread criticising the Perot presidency’s “backwater, nationalist, nigh on xenophobic” stance on Chinese import tariffs: Perot has heard it all and ignored it all.

Ross Perot, of Texerkana, Texas, was the rare case of a billionaire better known for his philanthropic work than his lifestyle, whether campaigning to rescue American POWs in Vietnam, or buying a 700- year old copy of the Magna Carta (worth $1.5 million) for the National Archives. He was also well-known for his political fixations. The Washington Post has openly savaged him for hypocrisy, self-aggrandizement, and mistruths in the Armitage affair, when Perot sought an official inquiry on, and funded a private investigation of, then-Assistant Defense Secretary Armitage on the basis of his connection to a Vietnamese woman. In their journalists’ eyes, he was a “hard-core conspiratorialist”, who had “bought into a plot in which drugs, Iran-contra[band], the CIA and POWs were all somehow connected”. Perot engaged in back-channel, unauthorized communications with Vietnamese officials during the Reagan White House. He later agreed to be their business representative if the diplomatic waters ever cooled. He was a bother to two administrations, a presumptous private citizen with money to burn, and convinced of his duty to his fellow Americans. He was, in other words, a political loose cannon. A loose cannon that then appeared on CNN live and announced – to an incredulous audience – that he would run for president if the American people would just get him onto the ballot in all 50 states.

The billionaire declared his determined, distinctive bipartisanship when he hired Democrat and Jimmy Carter’s ex-Chief of Staff, Hamilton Jordan, alongside Ed Rollins, Republican campaign director for the Reagan administration. He was for the American people – and for Perot, that meant appealing to all of them, red or blue. Luckily, he was aided in broadcasting this message. With Rollins came the all-important man of myths, Hal Riney. “Morning in America”, the slogan that swept Reagan to power, had been Riney’s great triumph, and now that brain was set to the task of electing one of the unlikeliest candidates of the 1992 race . Evident in the campaign staff was not just Perot’s willingness to work across the political aisle, but also his startling capacity to pull powerful and influential political veterans to his side. By May 1992, the image of his solemn but intent gaze was spread across the nation on the Times’ latest cover: Waiting for Perot.

And Perot’s charisma – understated, intense, with sharp bites of wit – would show to be utterly compelling as the race grew more intense. In October, just a month before the final election, the Perot campaign began running half-hour infomercials – veritable lectures on economics and Perot’s policies, all in his slow, intent Texan drawl. And they did well. Startlingly well. Perot’s infomercials drew larger regular audiences than most sitcoms.

It was this charisma which had been Perot’s saving grace way back in July, just as his intensity was nearly his undoing. Clinton had just received a boost in the polls from the Democratic National Convention, and the main party machines were beginning to grind onto the election circuit. Newspapers kicked into election mode with them, and Perot’s United We Stand campaign couldn’t hide the cracks under the increased scrutiny. There were reports that volunteers in Perot’s campaign were being required to take loyalty oaths; worse, there were rumbles of discontent from the upper levels of the campaign – Perot’s steeliness was alienating his powerful, high-profile supporters. Some said he had a compulsive need for control; others murmured that his policy vagueness was frustrating the best efforts of his campaign managers. The Chicago Times wryly noted “Perot may be an example of that rare breed of independent who, rather than having to be pulled down to earth by cooler heads, may need to be coaxed out of his burrow and convinced to show his colors.”

Later that week, the Republican and Democratic campaigns probably wished that he’d stayed in his burrow for a little longer. Perot offered CNN a live interview, rare since the inception of his campaign; his next announcement then proceeded to blow poor Clinton (already a C-list candidate) out of the headlines.

Perot set forth his entire economic plan, live on air, including achieving a gradual 50-cent tax in five years on every gallon of fuel – a measure that would cost the average citizen an extra $10 per tank.

The Democrats, enraged, accused Perot of attempting to squash middle-and-low income earners under the foot of a balanced budget. He thanked them for their staunch defense of the middle class, spoke about the necessity of American sacrifice, and then offered to increase his planned 33% marginal income tax to 35%, now that he knew he could rely on the Democrats to make the rich do their part. This became the archetype of his presidency’s classic Perotian maneuver, as he played on his twin strengths: an utter inability to compromise and a keen sense for a vulnerable underbelly.

The rumored rumblings disappeared as rumored rumblings often do, but whatever campaign chaos had forced Perot’s hand had done its damage. Perot’s polling took a hit in nearly every state as his uncommonly early policy platform delivered his opposition simply more solid ground upon which to open season on his candidacy.

Republicans deplored his hippie environmental sensibilities while nervously watching their constituencies for flickers of interest in Perot’s no-nonsense, at-all-costs commitment to balancing the books. They must have been, also, privately worried that Perot’s all-consuming focus on the economy would blind their normal base to his less appealing aspects, like his unequivocal commitment to a woman’s right to abortion, or his support of same-sex marriage. They even somewhat successfully managed to steer attention to his social beliefs throughout August and September, at the cost of not having quite as much time to rail against his tax agenda.

Yet October hit, and both Clinton and Bush had to offer their visions for the future, and the tables turned. Clinton was discovering, to his dismay, that all the Republican rhetoric about Perot’s degraded values had sounded quite appealing to his more socially liberal allies, and an entire wing of his party had peeled off to the independent without Perot lifting a finger. Meanwhile, some of Clinton’s essential moderate voters were slipping through his grip and tuning into Perot’s infomercials.

Perot entered the presidential debate polling at 20% of the vote, up from a post-July low of 17%. Bush and Clinton were still obviously the front-runners, and clearly considered themselves the serious contenders. It was high stakes for both of them: Bush only held a wafer thin lead over his challenger.

They needn’t have worried.

Bush fudged. Clinton proclaimed. Perot was funny. Bush hedged around what made him worth voting for after his recession-riddled presidency, Clinton waxed eloquent about change and his own qualifications, and Perot cut through all six minutes of that, sharp as a knife, with “It’s true, I don’t have any experience running up a 4 trillion dollar debt” to a whole room of laughter.

In his supremely sincere fashion and with a gift for quippy soundbites, Perot dominated both the first and third debates, bouncing up by 8% in his polling to a solid 28%. He was nipping at Clinton’s heels as Clinton breathed down Bush’s neck. It was, to quote a venerable journalist, “the bizarrest conga line in US electoral history”. Yet Perot was still in third place – possibly the most successful third party candidate in history, but still, unhappily, third.

November 4th 1992, the nation counted out its votes. Murmurings around the country swelled to a tsunami tide, and late into the night, families gathered around the TV as the election narrowed to a dead heat. The vote count climbed and the presidency was balancing on a knife edge. Perot was outperforming his polling by several percentage points, an unexpected disaster for the Democrats – yet the Republicans cursed him too, as many of their swing states turned Perot. We slowly, collectively realized that Ross Perot – the dark horse, the outsider, the socially radical economic conservative, the antithesis of establishment – might actually win the presidency of the United States of America.

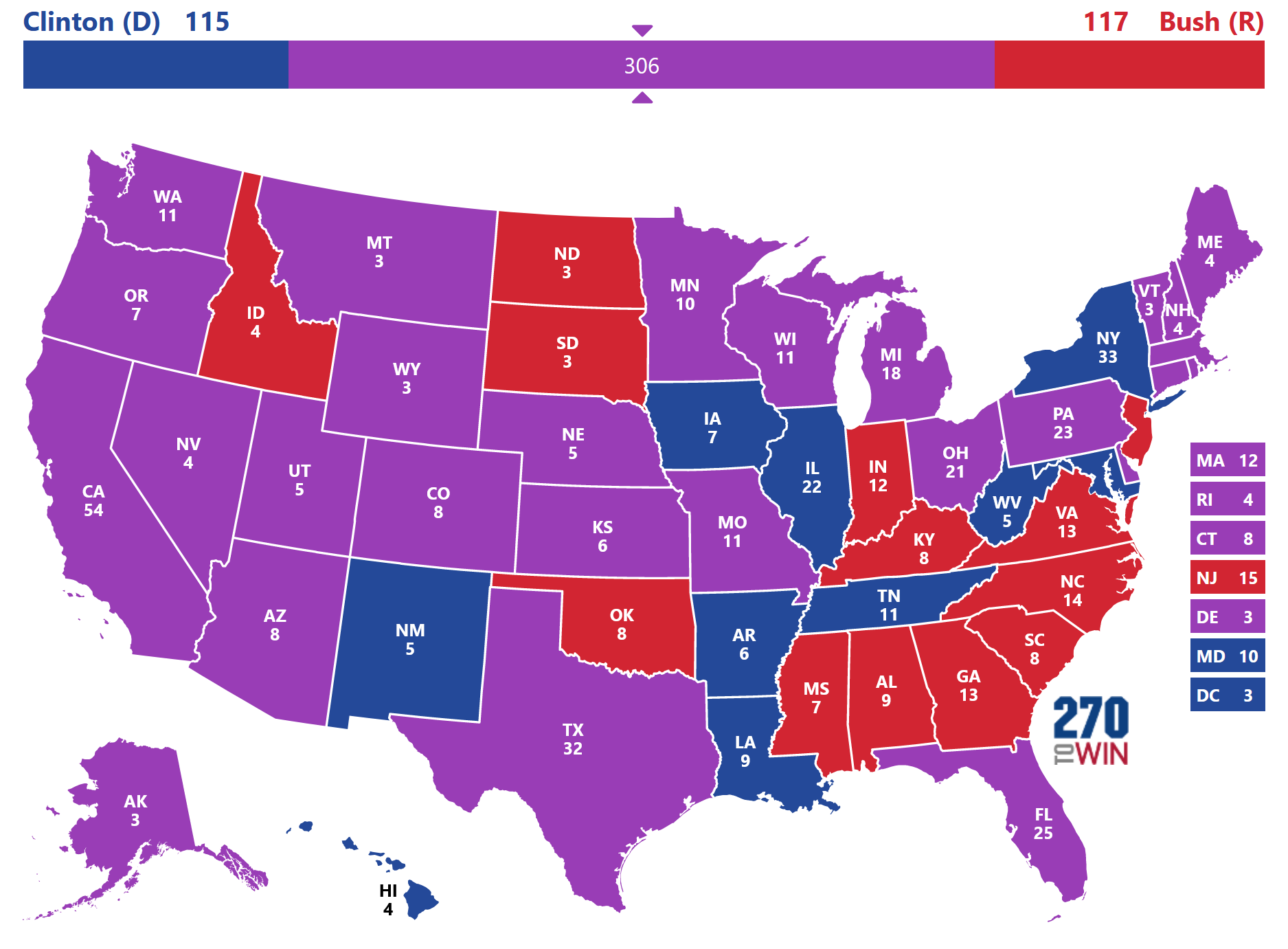

Yet Perot still only pulled 30.6% of the vote; Clinton came in ahead of him with 34.6%; and Bush beat them both, at 34.9%. However, while in another, more democratic country, that might have been the end of it, the race was not over yet; in our ever-exceptional United States, it is the Electoral College that decides the president. And Perot, unbelievably, to everyone’s astonishment, had spread his message just right, and managed to net 306 Electoral Votes, a winning majority, with less than a third of the vote.

(Perot: Long Shot or Unprecedented President? – see how Perot actually could have won)

As the votes tallied up across the nation, the states of America, one by one, flipped to their third-favorite son. By 11am on November 6th, both Bush and Clinton, dumbstruck, stumbled through numb concession speeches.

It was morning in a new America.

Chaos ruled the newspapers and the streets. Perot supporters held impromptu parties on street corners and in parks. Frequently, journalists were told that “We feel like we actually got a choice in the election – we didn’t just have to take what the Dems or Republicans gave us. ” and “This is real democracy, man.” On the other side, the ceremonial death of democracy was being given the final touches in newsrooms and editors’ offices as they declaimed how a man who hadn’t even scraped a third of the vote total was now the Commander-in-Chief. Both major parties lost their minds, any sense of usual policy, and frankly, any political convictions. Losing to each other was bad enough, but to a “third-rate, third-place outsider”?

In having conquered the establishment, many feared that Perot might have – and might still – spell its end. The Electoral College had handed the victory to runner-up candidates before, but never to such a blatantly unrepresentative winner.

The Republicans, previously staunch defenders of the sacred originality of American democracy, immediately started agitating for Electoral College reform. The Democratic Senator from Vermont was recorded saying that “between a two-party Capitol and a third-party President, I know who’s going down in flames.”, and a bitter vice-presidential candidate Al Gore unwisely remarked that Perot’s historic presidency would be “historically useless” if he didn’t have the Senate. However, considering that many of their constituents had voted for Perot, other Democrats rebuked their brethren for being unwilling to represent the spirit of their districts. This was less principled behaviour and more political opportunism. After all, a disproportionate number of Democratic Senators were up for re-election in two years, and, as they had so warningly pointed out to their fellows…their states had turned strongly to Perot.

Needless to say, Perot accomplished unusually little in his first 100 days, between the grinding resentment of both Republicans and Democrats. NAFTA, a free trade deal with Mexico and Canada that had been in the works with the previous administration, was dismissed by Perot before it even hit his desk. All in all, his only significant achievement was managing to cap Medicare with the support of the Republicans. Supreme Justice Byron White retired, and in a nod to the large chunk of socially-liberal voters he had peeled off the Democrats, Perot nominated Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a moderate who had been heavily involved in gender discrimination lawsuits. She was the second woman, and first Jewish woman, ever appointed to the Supreme Court, and won her confirmation by 96-3 votes. She was also yet another example of Perot’s ongoing efforts for bipartisanship, having been recommended by both Republican Senator Orrin Hatch and Perot’s Democrat-leaning Attorney General, confirmed just earlier that year.

With 35 seats up for grabs in the 1994 Senate elections, Perot was finally able to make some headway. He had formed his official party, the United Party, and they set to work in every state in the race. Perot constituted a viable threat to many of the seats up for re-election, and campaigned endlessly on behalf of his candidates. It paid off in a landslide. Of the 12 seats where Perot had scored a margin of 2% or better, he won nine. He took a further 3 states loyal to him since the presidential election, and then pulled six seats off the Democrats from states that had voted Clinton. Throughout the past two years of frustration, incapable of achieving anything on the Hill, Perot had thrown his efforts into turning the narrative on the “stubborn, pig-headed, self-interested and self-promoting” inhabitants of the Capitol. He had endlessly imprinted into his voters that one president wasn’t enough – that reform came from an entire country united for reform, and that meant uniting the arms of the government as well.

Uniting them, that was, by making them advocates of Perot.

In total, Perot won 21 of 100 seats, taking 12 off the Democrats and 9 from Republicans. Another 3 independents in Virginia, New Jersey and Ohio managed to beat out their major-party counterparts; the Senate elections of 1994 had become a frenzy of independents like never before. Perot’s win had put hope for political diversity back into the country again; and try as he might, he could not channel it all to his purposes.

With the Senate standing D-38, R-38, U-21 and I-3, the Senate was now spliced into three unstable major powers, and Perot finally had the power and bargaining room he needed to deliver on his aging promises. Legislation increasing marginal tax rates and broadening the dictate of education passed quickly. The Uniteds soon managed to get further protections for the environment set it, in a compromise that gave the Republicans many of the business deregulations they had been seeking. Perot wrangled and bargained and pushed and threatened, and finally got a five-cent tax on gasoline squeezed through – less than he had hoped for, but more than the old administration had ever dreamed of giving.

Going into this election, Perot stands on his record of having taken power as an underdog, solidified power as a president, and having passed much of the major economic legislation that was his overwhelming focus. It’s the greatest shake-up of American politics in living memory. The economy has boomed, revenue has increased, and in the past two years since the Senate sweep, the deficit has slowly, gradually narrowed. Perot has been blessed with an unusually uneventful presidency, refused all involvement in foreign wars, continually frustrated the EU, and focused as exclusively as the leader of the greatest world power can on domestic politics. He has not yet spelt the death of the Electoral College – that American institution still lives on strong, much to his advantage. His competitors face a map that has already shown a propensity to skew to Perot’s favor.

As for his competitors? Dick Gephardt is qualified particularly by his home state Missouri’s fidelity to the Democrats in times where other states have allowed themselves to be scandalously seduced away to Perot. He runs as the last hope for his party’s legitimacy, campaigning in former blue heartland to retake the jewels of the Democratic voter base before his party enters the classic minor-party death spiral. If their remaining voters sense that they will be voting for a lost cause, they will doubtlessly jump ship to Perot, and the death of the Democratic Party will be swift. Their doom lurks in their shadow, and so they steam ahead with unmerited certainty and a certain steely-eyed panic. Thankfully, the appropriate pomp of funeral arrangements and attire will be guaranteed by the presidential balls.

Perot’s other challenger, out to take his presidency and not his voter base, is John McCain. The rare Republican who could actually stand to challenge Perot on all his strengths, McCain is a “straight-talking”, gregarious, quick-footed thinker, who has shown regular enjoyment when jousting with journalists and possibly delight in his campaign staff’s inability to control him. He’s universally known as “the maverick”, championing a reform-oriented conservatism, an astounding faith in his party, and a sincere desire to reach out to independents. Perot may wish that he’d stop reminding everyone that there are other bipartisans on the block. With McCain, the Senate Dem-Rep alliance may also be showing more unity than Perot’s fractious party of personalities, and it’s not exactly like Perot’s sparkling wit is getting full reign against this honest-to-goodness former prisoner of the Vietnam War. Perhaps this is vengeance for the 15 lost Senate seats: one wonders how else the Republicans were so motivated to give Perot an opponent who was merely an upgraded, veteran, conservative version of himself.

The coming election will likely decide the fates of the three parties, the posterity of Perot’s unprecedented presidency, and the shape of politics for years to come. So tune into your Perot infomercials, hustle out to a McCain town hall, listen idly to Gephardt over the radio, and vote, ladies and gentlemen, on our upcoming, most momentous, November 4th. It’s the last election of the millennium; no doubt it’ll go out with a bang.